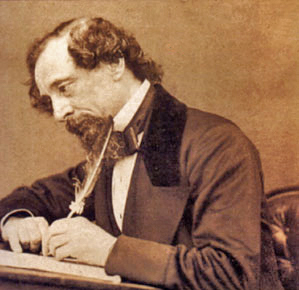

Charles Diekens - retrato

Victorian literature

Victorian literature is the body of writing produced during the reign of Queen Victoria (1837—1901) and corresponds to the Victorian era. It forms a link and transition between the writers of the romantic period and the very different literature of the 20th century.

The 19th century saw the novel become the leading form of literature in English. The works by pre-Victorian writers such as Jane Austen and Walter Scott had perfected both closely-observed social satire and adventure stories. Popular works opened a market for the novel amongst a reading public. The 19th century is often regarded as a

Significant Victorian novelists and poets include: the Brontë sisters, (Anne, Emily and Charlotte Brontë), Robert Browning, Elizabeth Barrett Browning, Edward Bulwer-Lytton, Lewis Carroll, Wilkie Collins, Joseph Conrad, Charles Dickens, George Eliot, Elizabeth Gaskell, George Gissing, Thomas Hardy, A. E. Housman, Rudyard Kipling, Robert Louis Stevenson, Philip Meadows Taylor, Lord Alfred Tennyson, William Thackeray, Anthony Trollope and Oscar Wilde.

Movement and change

The great social changes that happened in Britain during

This new readership dictated a change in the methods of authors. For much of their history authors had worked for literary patrons, rich individuals who would fund an author's working life and effectively 'reward' a writer with money, gifts or positions for their latest book. This patronage by a few wealthy people tended to limit the range and style of works produced. The rise in a broader reading audience meant that the author could make a living selling their work on the open market to the public at large. This meant not only an explosion of readers but also of writers catering to the varied tastes of the time. Although a greater range and proliferation of work abounded the author was often no freer from the whims and moods of his readers in the general public then when controlled by a wealthy patron.

The prevailing method of publication to reach a wider audience was serialization in regular literary journals. This gave the reader a series of short episodes, usually in weekly or monthly installments, each with their own cliff-hanger which heightened expectations and made the purchase of the next installment a must. While the average substantial work had about twenty parts, there could be as many as thirty-five: usually with illustrations of key scenes by artists like Phiz (pseudonym of Hablot Knight Browne). Punch and Household Words were two such journals. Once the entire story was serialized, the parts were combined into a complete work; the work would then (usually) be published as a three-volume novel rather than a single book. Despite the constraints of this form, many great novels were published in this manner (e.g., all of Dickens' major works were published serially.)

The three-volume structure was promoted by Charles Mudie's library "Leviathan". This was an early subscription library, and one of the most popular. For a small fee, much less than it would cost to purchase a book outright, a reader could borrow the latest novel or non-fiction work. This added to the popularity of novels and reading, and by the 1850s Mudie had almost 950,000 volumes. Owing to his importance in this new industry, Mudie was in a position to dictate the plot of many works; this is apparent in the 1890s when Mudie's business floundered and the number of works published in three volumes dropped to almost none. In addition to the prevalence of the three-volume format, Mudie is sometimes blamed for the frequency of happy endings in Victorian fiction.

Novelists

Charles Dickens exemplifies the Victorian novel better than any other writer. Extraordinarily popular in his day with his characters taking on a life of their own beyond the page, Dickens is still the most popular and read author of the time. His first real novel, The Pickwick Papers, written at only twenty-five, was an overnight success, and all his subsequent works sold extremely well. He was in effect a self made man who worked diligently and prolifically to produce exactly what the public wanted; often reacting to the public taste and changing the plot direction of his stories between monthly numbers. The comedy of his first novel has a satirical edge which pervades his writings. These deal with the plight of the poor and oppressed and end with a ghost story cut short by his death. The slow trend in his fiction towards darker themes is mirrored in much of the writing of the century, and literature after his death in 1870 is notably different from that at the start of the era.

William Thackeray was Dickens' great rival at the time. With a similar style but a slightly more detached, acerbic and barbed satirical view of his characters, he also tended to depict situations of a more middle class flavour than Dickens. He is best known for his novel Vanity Fair, subtitled A Novel without a Hero, which is also an example of a form popular in Victorian literature: the historical novel, in which very recent history is depicted. Anthony Trollope tended to write about a slightly different part of the structure, namely the landowning and professional classes.

Away from the big cities and the literary society, Haworth in West Yorkshire held a powerhouse of novel writing: the home of the Brontë family. Anne, Charlotte and Emily Brontë had time in their short lives to produce masterpieces of fiction although these were not immediately appreciated by Victorian critics. Wuthering Heights, Emily's only work, in particular has violence, passion, the supernatural, heightened emotion and emotional distance, an unusual mix for any novel but particularly at this time. It is a prime example of Gothic Romanticism from a woman's point of view during this period of time, examining class, myth, and gender. Another important writer of the period was George Eliot, a pseudonym which concealed a woman, Mary Ann Evans, who wished to write novels which would be taken seriously rather than the silly romances which is all women of the time were supposed to write.

The style of the Victorian novel

Virginia Woolf in her series of essays The Common Reader called George Eliot's Middlemarch "one of the few English novels written for grown-up people". This criticism, although rather broadly covering as it does all English literature, is rather a fair comment on much of the fiction of the Victorian Era. Influenced as they were by the large sprawling novels of sensibility of the preceding age they tended to be idealised portraits of difficult lives in which hard work, perseverance, love and luck win out in the end; virtue would be rewarded and wrong-doers are suitably punished. They tended to be of an improving nature with a central moral lesson at heart, informing the reader how to be a good Victorian. This formula was the basis for much of earlier Victorian fiction but as the century progressed the plot thickened.

Eliot in particular strove for realism in her fiction and tried to banish the picturesque and the burlesque from her work. Another woman writer Elizabeth Gaskell wrote even grimmer, grittier books about the poor in the north of

This change in style in Victorian fiction was slow coming but clear by the end of the century, with the books in the 1880s and 90s more realistic and often grimmer. Even writers of the high Victorian age were censured for their plots attacking the conventions of the day with Adam Bede being called "the vile outpourings of a lewd woman's mind" and The Tenant of Wildfell Hall "utterly unfit to be put into the hands of girls". The disgust of the reading audience perhaps reached a peak with Thomas Hardy's Jude the Obscure which was reportedly burnt by an outraged bishop of Wakefield. The cause of such fury was Hardy's frank treatment of sex, religion and his disregard for the subject of marriage; a subject close to the Victorians' heart, with the prevailing plot of the Victorian novel sometimes being described as a search for a correct marriage.

Hardy had started his career as seemingly a rather safe novelist writing bucolic scenes of rural life but his disaffection with some of the institutions of Victorian Britain was present as well as an underlying sorrow for the changing nature of the English countryside. The hostile reception to Jude in 1895 meant that it was his last novel but he continued writing poetry into the mid 1920s. Other authors such as Samuel Butler and George Gissing confronted their antipathies to certain aspects of marriage, religion or Victorian morality and peppered their fiction with controversial anti-heros.

Whilst many great writers were at work at the time, the large numbers of voracious but uncritical readers meant that poor writers, producing salacious and lurid novels or accounts, found eager audiences. Many of the faults common to much better writers were used abundantly by writers now mostly forgotten: over-sentimentality, unrealistic plots and moralising obscuring the story. Although immensely popular in his day, Edward Bulwer-Lytton is now held up as an example of the very worst of Victorian literature with his sensationalist story-lines and his over-boiled style of prose. Other writers popular at the time but largely forgotten now are: Mary Elizabeth Braddon, Charlotte Mary Yonge, Charles Kingsley, R. D. Blackmore and even Benjamin Disraeli, a future Prime Minister.

www.wikipedia.org